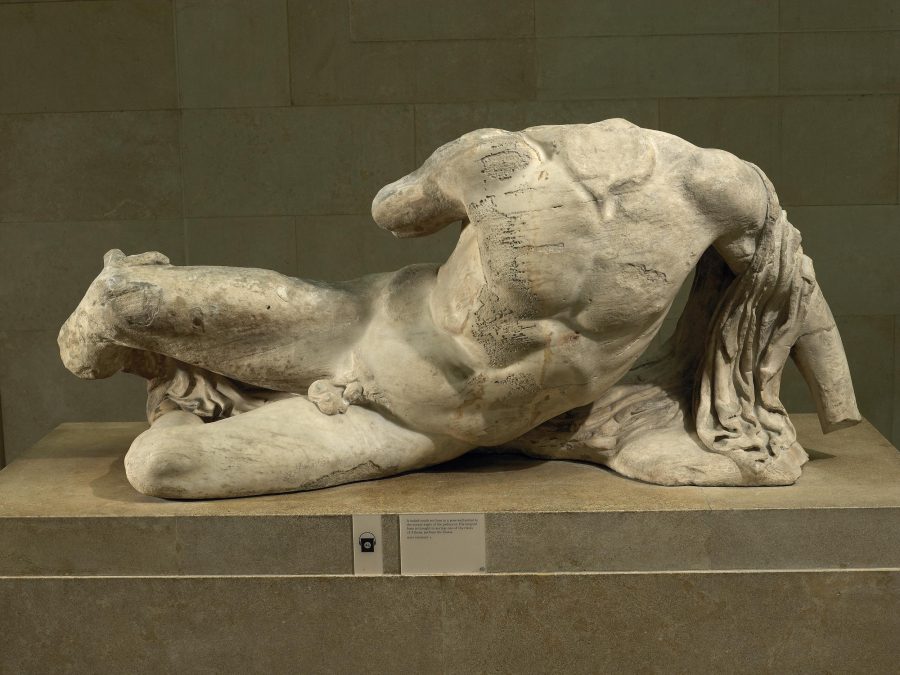

The Parthenon ilissos

Here is the Ilissos from the Parthenon, sculpted by Pheidias around 430 BC. Charles Bargue chose it for plate no. 62 in the section Modèles d’Après la Bosse (which means after sculptures).

The very title of this sculpture, and therefore that of the plate, is purely hypothetical. The Ilissos or Ilissus was a river that flowed around Athens. Nowadays, this river is almost entirely channelled and underground, and its irregular flow only very rarely leads to the sea. But you can well imagine the importance of living water in ancient times. It’s hardly surprising that gods might have been the image of this natural wealth. The sculpture probably represented a god emerging from the river, as the arms and legs are supported in an attitude that suggests emerging from the water and rising again.

We can, of course, speculate on the attitude this man had before losing his legs, head and arms.

This is where a curious image brings us a piece of history…

Take a look at this painting by Théodore Lancelot in 1804.

We know that Bargue didn’t draw his Ilissos looking at the west pediment of the Parthenon – he wasn’t there any more! But in any case, in 1804, he was still there…

This view of the west pediment of the Parthenon shows the Ilissos. It was placed on the left-hand side, in the narrowest part of the triangle. But it looks as if the head was already missing. We therefore have to look for other images to find out when the Ilissos lost its limbs and its head.

This illustration from a 1910 encyclopaedia still shows it in one piece, but it was a sort of fanciful reconstruction…

In the early 19th century, Edward Dodwell produced this watercolour showing the removal of the Parthenon marbles.

More unrealistic than ever, this watercolour shows blocks weighing several tonnes being supported by just two men, while the rope is not even taut! It is therefore impossible to believe that the Parthenon was ever dismantled in this way, even though most of the marble sculptures were indeed dismantled at some point, since most of them now sit in the British Museum.

The British Museum has produced a beautiful reconstruction that gives a fairly accurate idea of what the sumptuous decorations of the Parthenon were like before the Ottoman domination, when damage was caused in no small measure.

At the ends of the pediment, to suggest the setting of the scene (the struggle between Athena and Poseidon for control of Attica), Phidias had placed the reclining statues of Cephisa and Ilissos, personifications of the two rivers of Attica.

So when did the Ilissos lose its arms and legs?

In this earlier illustration attributed to Jacques Carrey, the Ilissos is already badly damaged.

Yet this drawing dates from 1674! So who broke the Ilissos?

It is likely that it was damaged at different times.

Firstly, during the Herulian invasion, but it would have been partially restored. Then the edict of Theodosius II in the 2nd century forced the closure of the Parthenon, which was converted into a Christian church. It became a mosque after the Turkish conquest.

Finally, in 1687, during the Moraean War, an ammunition depot was placed inside, and during the siege of Athens, the Venetians bombarded the Parthenon, bringing down the central part. The marks of these bombardments can still be seen today.

At the beginning of the 19th century, a delegation obtained the right to finish depositing the sculptures, which after passing through private collectors ended up in the British Museum, the Louvre and a number of other places.

Could the Ilissos have escaped all this?

And now, if the Ilissos has won you over ...

We have a great opportunity for you:

The Ilissos is one of the rare plates for which Bargue did not adopt the laid paper effect found among the majority of the other plates.

This gives it an extra velvety, satin-finish effect that only lithography can reproduce, and is a good match for the polished marble subject.